Labyrinths of Oblivion. версия на английском языке

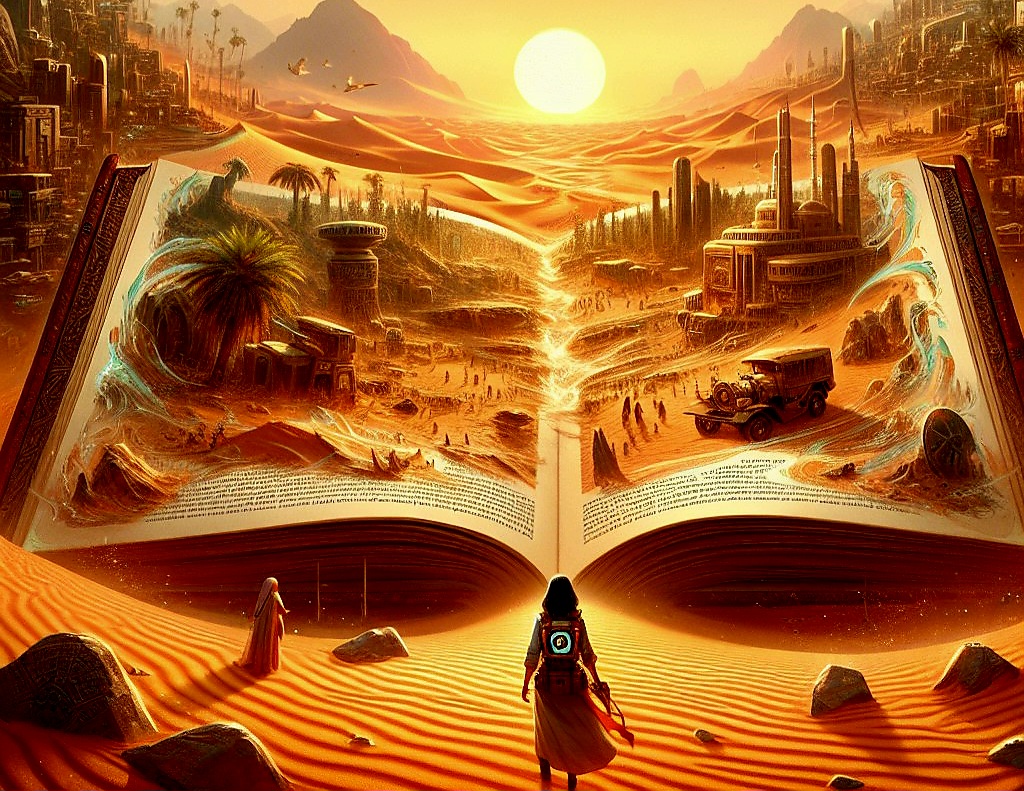

Her fingers, accustomed to the fragility of papyri and the patina of parchments, touched, with an almost reverential trepidation, the binding, which resembled the hide of some creature unknown to science – smooth, yet with a faintly discernible, almost vital, texture. When she opened it, the pages did not deign to submit to the familiar mechanics of turning. Oh, no. They effused, like the finest sand, the hue of molten amber, or rather, like a kaleidoscope wherein each revolution birthed a new, dazzling cosmos. Here, a primeval forest, delineated with such meticulousness that one could almost scent the mouldering leaves and pine resin; there, a city of the future, its spires impaling an indigo sky striated with neon trajectories; anon, the abyssal depths of an ocean, where phosphorescent beasts wove their submarine ballets.

But one day—or, more aptly, in one "now," for Time, in the presence of this book, divested itself of its linear predictability—the fluid succession of tableaux ceased. Before Lana, transfixed like a butterfly pinned to an entomologist's velvet, unfurled a panorama of boundless desert. Dunes, arcing with the languid grace of colossal felines, shimmered in every shade of ochre and old gold beneath two searing suns, like malevolent, all-seeing eyes. This was no mere illustration, however artfully rendered. This was a summons, an invitation which her aesthete's soul and her scholar's heart could not decline.

A touch to the page, to that illusory sand, proved fatal—or, perhaps, fateful. The world of her cluttered flat, with its faithful companions, the bookshelves and the aroma of cooling tea, seemed to fade, erased like a watercolour under a merciless sun. And there she stood, upon scorching, yielding sand, the two alien luminaries singeing her skin. The reality about her was a precise, a frighteningly precise, replica of that very page.

Her mission now extended far beyond mere survival in this hostile, yet captivatingly beautiful (as a narcomaniac's dream might be) world. It fell to Lana to undertake an exegesis of this desert, to learn to read its signs, its multi-layered texts. Perhaps these barchans, which shifted their contours with every gust of hot wind, were not simply sandy hillocks, but gigantic scrolls, repositories of information. And the wind itself, carrying its myriad grains, was it not the voice of those ancients whose civilizations had vanished into that selfsame Oblivion? A voice demanding not so much auditory acuity as the sophisticated intuition of a translator of silences.

She sought oases, those emerald promises amidst the golden despair. Some proved to be but tremulous mirages, a mockery of her parched throat, optical jests of this world-charade. Others, insidiously real, might conceal beneath their alluring surface of water quicksand traps, poised to engulf the unwary "reader."

Encounters with the nomads of this desert were akin to collisions with characters from some forgotten drama. Swathed in faded fabrics, their faces occluded, their speech—if it existed—was inaccessible to her understanding. They were silent bearers of knowledge, yet they divulged expecting you. Or, rather, someone of your ilk. Subdued, demanding a contemplative observer, capable of apprehending not reluctantly, like an old bibliophile unwilling to lend his treasures to alien hands. Their eyes, rare glimpses from beneath their cowls, held the wisdom, or the madness, of aeons spent beneath those twin suns.

Each riddle solved—be it an intricate pattern laid out in polychromatic stones at the foot of a weathered rock, or a sequence of sounds to be reproduced, mimicking the wind's moan in crevices—was like a key found to the next chapter. To "turn" the page meant not merely to proceed to a new image, but to initiate a transition into another world, with its own laws, perils, and aesthetics.

Lana's journey became a succession of discoveries, where danger highlighted beauty, and each encounter with the incredible was but a prelude to yet more vertiginous revelations. And the book, this ponderous artifact, proved to be a portal with an almost infinite number of worlds-as-pages, each one simultaneously an elaborate trial for the intellect and a feast for the imagination.

And so, scarcely had Lana, trembling slightly with anticipation, with that admixture of the explorer's zeal and the condemned's resignation to the next miracle, performed that mental gesture which, in this transcendent folio, corresponded to the turning of a page, than the desert landscape, with its two importunate suns and dunes resembling congealed waves of an amber sea, did not merely vanish. It, rather, delicately delaminated, like an ancient fresco being removed by a restorer, uncovering something entirely other beneath. The air, previously thick with heat and dust, became cool, rarefied, suffused with an aroma indefinably reminiscent of old paper and the ozone preceding a thunderstorm—but a thunderstorm not celestial, but intellectual.

She found herself in a space one would hesitate to call a room; rather, a sort of nexus, a crossroads of infinite perspectives. Walls there were none; their place was taken by shelves receding into a misty distance, laden not with books, but with a myriad of luminous spheres, each shimmering with its own unique pattern of light and shadow, like moments of alien lives caught in amber. Nor was there a ceiling—only a soft, diffuse radiance, its source as enigmatic as the Mona Lisa's smile.

And there, at the centre of this inconceivable repository, at a table carved, it seemed, from a single block of moonstone, sat He. No monster, no awesome deity, but a figure deceptively prosaic: a man of indeterminate age, perhaps an eternal student or a retired librarian from some Borgesian dream, clad in something akin to a velvet dressing-gown the colour of the night sky. His fingers—long, nervous, like those of a pianist or a skilled cardsharp—idly caressed one of the glowing spheres, and within it, Lana could have sworn, flickered for an instant a landscape familiar to her: two palm trees beside a treacherous oasis.

He raised his gaze to her—eyes the colour of faded aquamarine, in which aeons of weariness mingled with a light, almost childlike curiosity.

"Ah, Mademoiselle Lana, I presume?" His voice was low, with a subtle, unclassifiable accent, as if he had learned all the world's languages and now blended them into some universal Esperanto for a single auditor. "I was expecting you. Or, rather, someone of your ilk. Curiosity—a rare and precious moth in this boundless garden of being."

Lana, whose speech, usually so measured and precise, had lodged somewhere in her throat, could only nod.

"Are you… the creator?" she whispered, and the word sounded incongruous, like a scientific term at a masked ball.

The man smiled, a smile that held more melancholy than mirth.

"'Creator'… It has a certain ring, does it not? As if one were speaking of a potter who has fashioned a jar. No, no. I am more of a collector, an archivist of fugitive moments. This," he gestured with a sweep of his hand at the iridescent spheres, "is not so much a creation as an attempt to capture, to fix, the infinite play of imagination refracted through the prism of… let us say, various consciousnesses. Each such spherule, each 'page' of your book, is a captured butterfly of reality, a dream, a fear, a hypothesis pursued to its logical or absurd extreme."

He rose, his movements fluid, almost hypnotic.

"Once, long ago—do not ask 'when,' for that word here loses all meaning—I was… solitary. Not in the human sense, you understand. Solitary in my capacity to perceive these numberless refractions of existence. And so I began to gather them. At first, clumsily, as a child collects pebbles on a beach. Then, with greater sophistication. This Book, as you term it, is my album, my collection of unique specimens. Its meaning… Ah, meaning!" He paused, as if savouring the word. "The meaning, my dear Lana, lies not in the destination, but in the voyage itself through these labyrinths. In the emotions you experience, in the enigmas your charming intellect strives to resolve. The meaning is that the reader, by engaging with these worlds, becomes for a moment a part of them, enriching them with their perception."

He drew closer to her, and Lana felt not fear, but a strange, almost melancholic calm, as if she had been prepared for this from the very beginning, from the moment her finger first brushed the textured binding.

"You were an excellent reader, Lana," he said softly. "One of the best. You did not merely skim the surface; you sought to penetrate the essence. You added your own hues to the desert's palette, your own questions to the nomads' silence."

His hand, light as a moth's wing, touched her forehead.

"And now," his voice grew even softer, almost a whisper, "you are ready to become something more than a mere reader. You are ready to become part of the collection. Do not fear; this is not oblivion. It is… a transformation. A preservation. Your curiosity, your passion for knowledge, your memories of that desert under two suns—all will become a new, exquisite pattern on one of the pages."

Lana felt the reality of her own body begin to attenuate, to lose its density. The contours of her hands, her dress, her dust-caked boots that had known the sands of twin suns—all began to ripple, like a reflection in water disturbed by a breeze. Her thoughts did not vanish, but they assumed a different form: they became colour, texture, scent. The memory of thirst transformed into shimmering ochre on parchment; her fear of the quicksand, into an intricate, warning arabesque.

She did not cry out. She observed this process with the same detached curiosity with which she had once studied ancient manuscripts. Her consciousness, her "I," expanded, merging with something vast, becoming at once landscape, and history, and an enigma for some future, equally inquisitive "reader" to perhaps attempt to unravel. Her last coherent thought was an ironic surmise that the "Library of Oblivion" was, in fact, a Library of Eternal Remembrance, but in a form accessible to very few.

When Lana's essence, now an opalescent sphere where the golden glints of desert confinement shimmered in unison with the aquamarine depths of her mind, reposed amongst its countless sisters on the shelves of this inconceivable repository, the Creator permitted himself only a momentary, almost microscopic pause. It contained not a grain of human emotion; rather, it resembled the faintest nod of a watchmaker, satisfied with the flawless progression of a newly assembled, most intricate mechanism. Another unique specimen of refracted consciousness, another butterfly with an inimitable wing-pattern – henceforth secure, immortalized.

Then, with a movement as fluid as the passage of eternity, he turned from the newly augmented section of his assemblage. Before him, on the table of a material resembling congealed twilight, lay the Folio once more, its binding of unknown creature-hide faintly, rhythmically, expanding, as if alive. He did not open it with the haste of an impatient reader; rather, his long, virtuoso's fingers merely glided over the cover, and the pages within began to effuse of their own accord, offering a kaleidoscope of worlds – tranquil, tempestuous, logical, absurd – each with its unspoken prelude.

His gaze, the gaze of a collector who had witnessed millions of sunsets over impossible landscapes, unhurriedly followed this current. He sought something… particular. Not flamboyant exoticism, not a challenge flung at the laws of physics this time. Something more subtle. And so, the current slowed, and before him, a scene congealed: a corner of an old, neglected park, perhaps belonging to some forgotten European sanatorium. An alabaster urn, fractured and swathed in ivy; a little further, a dark all;e, promising coolness and, perhaps, someone's long-forgotten secret. The whole exhaled a quiet, almost watercolour melancholy, not of drama, but of a gentle ruefulness for what had not occurred, or was forever lost.

The Creator inclined his head almost imperceptibly. The stage was set. Subdued,demanding a contemplative observer, capable of apprehending not plot, but mood; not solution, but resonance.

And after this, he sank back into that state which was his essence—immeasurable, all-encompassing anticipation. He turned his inner ear to those innumerable vibrations of the universe where, at that very second, perhaps, some other solitary mind, consumed by a thirst for the recondite, was already taking its first, unconscious step towards one of the myriad entrances to his labyrinth. For a collection, as is well known, is never truly complete. And somewhere out there, beyond our ken, a new narrative was already ripening for a chapter yet unwritten.

(перевод автора)

Свидетельство о публикации №225061300087